The Meaning of Artificial Life

Korean Media Arts Festival 2019

Sylvia Wald and Po Kim Gallery

417 Lafayette Street, New York NY 10003

August 8 to October 26, 2019

Open Tuesday to Saturday 11AM to 6PM

http://www.kmaf.us

In his 1946 short story “On Exactitude in Science”, Borges imagined a fallen empire whose cartographers were so precise that their map of the realm was the same size as the territory itself. The map crumbled alongside the empire until all that remained were a few tatters in the desert. Baudrillard used this story as the starting point for his book Simulacra and Simulation: “Simulation is no longer that of a territory, a referential being or a substance. It is the generation by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreal. The territory no longer precedes the map, nor survives it. Henceforth, it is the map that precedes the territory.”

Installation view of Infranet by Haru Ji and Graham Wakefield. Image courtesy of the gallery.

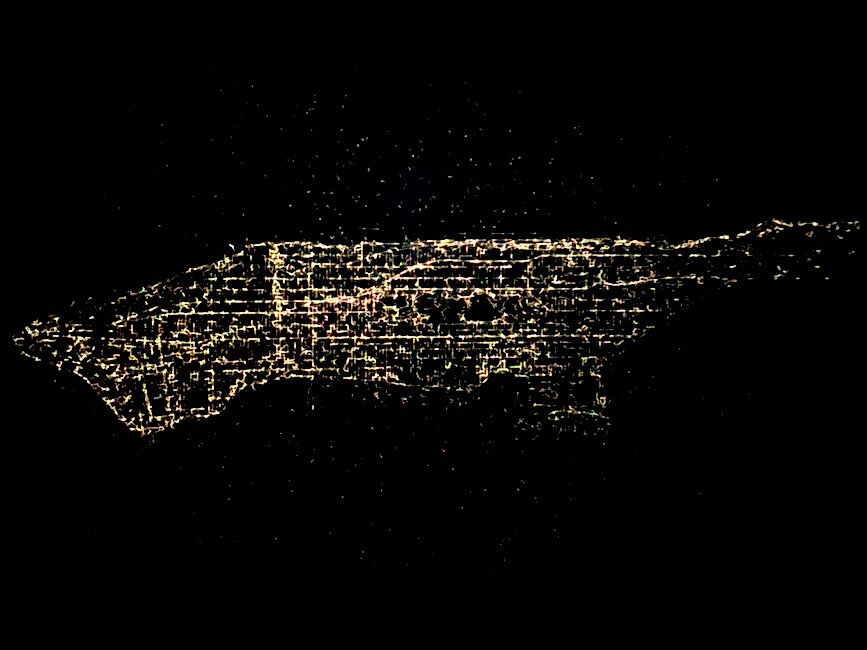

On view at the Korean Media Arts Festival at the Sylvia Wald & Po Kim Art Gallery is Infranet, an installation by Haru Ji and Graham Wakefield, in a section of the show called “living data”. The only light in its darkened corner comes from the projections on two of the space’s walls. The left wall shows a grid of “locations”, snapshots of digital cells growing, connecting, and dying alongside numerical statistics representing this in another form: percentages of “health” and “divergence”. The grid of locations resembles a large-scale surveillance setup, a wall of monitors allowing a single observer to see from every point of view at once. The projection on the right represents these locations from a different perspective. A pulsating mass of colored energy fills the screen. According to the artists, “[w]ithin this landscape of city data, artificial lifeforms are born, dwell, and die. The varieties of kinds of data in the city become resources of metabolism to the taste of each creature. Each one explores according to its unique neural network, through which it can carry ideas to share with others.” The camera rotates, pans, and zooms until the larger view of these creatures is revealed: this energetic mass is shaped exactly like Manhattan.

Installation view of Infranet by Haru Ji and Graham Wakefield. Image courtesy of the gallery.

Infranet uses, according to the wall text, a combination of two simulation technologies: artificial life (AL) and artificial intelligence (AI). The latter gets no shortage of media attention today, as AI technology is used in practically everything developers can force it into. AI, specifically artificial neural networks (ANN) has grown from a niche research field to a tech industry cornerstone in the space of a decade or so. Trevor Paglen had a show of art about—and created by—AI at Metro Pictures in 2017. Part of the exhibition included Megalith, a massive print depicting a training set of tiny handwritten numbers used to teach an AI to read bank checks. A more recent project, by Paglen and Kate Crawford, involves the ImageNet dataset, a decade-old “gold standard” for AI training. ImageNet Roulettewas an ANN that has been trained exclusively on ImageNet’s “people” category, and the bizarre and sometimes offensive identifications made by this AI speak to the impossibility of categorizing humanity in a computer-readable form without the influence of human bias. In principle, a well-trained AI, having gorged on mountains of data, can recognize familiar patterns in any new data given to it, although as Paglen and Crawford show, these identifications are not made in a vacuum. Data flows inward, from a large training set to the ANN’s tagged and supposedly recognized output.

Trevor Paglen, Megalith, 2017, pigment print,

82 1/2 x 72 inches. From Trevor Paglen: A Study of Invisible Images at Metro Pictures, September 8 to October 21, 2017. Image courtesy of the gallery.

AL hasn’t made as big of a splash in the mainstream as AI. It remains a research tool for biologists and computer scientists to model organisms and populations, but also finds use in videogames and art. Lev Manovich, in his book The Language of New Media, used a genetic metaphor to characterize AL’s creative potential: “In the AL approach, the interaction between a number of simple objects at run time leads to the emergence of complex global behaviors. These behaviors can only be obtained in the course of running the computer program; they cannot be predicted beforehand. […] The initial data provided by the program acts as a genotype that is expanded into a phenotype by the computer.” AL approaches can produce incomprehensible quantities of data from a small seed: the recent game No Man’s Sky used procedural generation to make eighteen quintillion possible worlds for the player to explore, each populated with unique life forms also created with AL processes. AL data flows in the opposite direction as in AI: possibilities explode outward from its simple rules and parameters.

Screenshot from No Man’s Sky by Hello Games, 2016, PS4 and PC. Image courtesy of the developers.

The exact AL processes used by Infranet are a mystery, although the cellular data shown on the left-hand screen resembles a Game of Life cellular automaton. AL represents an explosion of possibility radiating out from a small core of data. AI is an implosion that brings together massive sets of known data and outputs its own recognition or modification of it. AL processes can be used to create entire worlds or universes from tiny bits of seed data. For Infranet, Manhattan is both the start and end point of the simulation. City data is run through AL and AI simulations until an image of the city itself emerges from it, miraculously unchanged.

It’s unclear exactly what data types were used to feed Infranet’s digital creatures. The wall text cites non-specific “open city data”, and the gallery assistant mentioned public health records, air quality, pest control, and flood levels as possible sources. During multiple viewings at different times, the life force circulating around the map was brightest on Broadway, Fifth Avenue, and along the Hudson waterfront. The lights grew dimmer above Central Park, and aside from a glimmering backbone along the Hudson, northern Manhattan might as well not exist. Only the areas infused with capital get the privilege of being called “alive”. In the logic of AL, everywhere else is either dead or was never alive at all.

Installation view of Infranet by Haru Ji and Graham Wakefield. Photograph by the author.

Infranet is a loop that ends where it begins: the city as data, a quantified simulation of life. Only part of this loop is visible, as the pulsating map on one wall and the grid of cells on the other. The exact processes through which city data comes to resemble the city itself are hidden within a conceptual black box, and without further information from the artists regarding their methodology all that’s left is speculation. Perhaps the tension between the two processes —AI and AL—plays a part in the transformation. AL allows data to explode outwards from simple starting parameters, but AI feeds on large quantities of data and constrains its output to what it can recognize. Could the city itself be so recognizable that it becomes a boundary that the permutations of artificial life cannot overcome? Are the biases inherent to the source data so deeply ingrained that life’s processes cannot begin to defy them?

Installation view of Infranet by Haru Ji and Graham Wakefield. Image courtesy of the gallery.

Looked at from this perspective, the fact that the program outputs an accurate map of Manhattan is more disappointing than astonishing. With all the variability and possibility that these simulations of life can create, we’re stuck with a map that depicts the city’s structural inequalities without offering any critique or proposing a means of overcoming these problems. If areas infused with capital are considered alive, and everywhere else is dark and dead, this sets up an allegory that privileges the city’s status quo to the exclusion of other, more divergent possibilities. Artificial life can create entire universes from a tiny data seed; it’s a shame that a technology with such revolutionary potential is stuck within the conceptual borders that define Manhattan.